A recent announcement by Indonesia’s Education Minister reignited a familiar debate: national exams are making a comeback in 2026, this time in a new format. After being abolished in 2021, the reintroduction of the Ujian Nasional (UN) is said to be part of an effort to re-establish educational standards across the country.

Reading this news brought me back to my own school days: the tense build-up, the relentless drilling, and the emotional toll those national exams carried. For many of us, UN was more than just a test; it was a gateway to a better life. And now, as policymakers weigh the pros and cons once again, the arguments sound all too familiar. Supporters say national exams are necessary to uphold academic rigor and discipline, arguing that without them, students and teachers grow complacent. Critics, on the other hand, highlight the deep inequalities they expose: how students in under-resourced schools are held to the same standards as those in elite institutions. They also argue that such high-stakes exams narrow the purpose of education itself, pushing both teachers and students to focus primarily on drilling exam content rather than fostering real learning. Subjects not included in the exam often get sidelined, and creativity or critical thinking skills take a back seat in classrooms obsessed with test scores.

This policy tug-of-war reminded me of an assignment I did for the Education Economics and Policy course in the second semester of my MPP studies at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, NUS. Together with my groupmates, we assessed China’s Gaokao system, arguably one of the most high-stakes national examinations in the world. The parallels are striking.

The Gaokao, short for ‘Gaokao Kaoshi’ or the National College Entrance Examination, is China’s annual standardized test taken by high school seniors. It serves as the primary, if not sole, pathway to enter the country’s universities. With no other major university admission channels, the Gaokao is essentially a make-or-break moment for millions. The exam spans two intense days, covering subjects like Chinese, mathematics, a foreign language (usually English), and either sciences or humanities, depending on the student’s track.

For many Chinese students, it is more than just a test, it is the narrow gate to a better life. In a country of 1.4 billion people, the Gaokao is designed to be the ultimate meritocratic filter. One exam, one score, one shot. In 2023, over 13 million students sat for it. Yet, only 5% were admitted to China’s top 100 universities. For these few, the rewards are significant: higher wages, social mobility, and often, a lifelong sense of achievement. But for the rest, the road narrows.

The original intention behind Gaokao was noble: to level the playing field and give every student, regardless of background, a fair chance. In practice, however, the picture is more complicated.

Where You’re From Matters

Imagine two students, one from Beijing and one from a rural province like Gansu. They both get the same Gaokao score. But the student from Beijing stands a higher chance of getting into a top university. Why? Because of regional quotas and the hukou (household registration) system, which tie students to their province of origin and, effectively, to their chances of success.

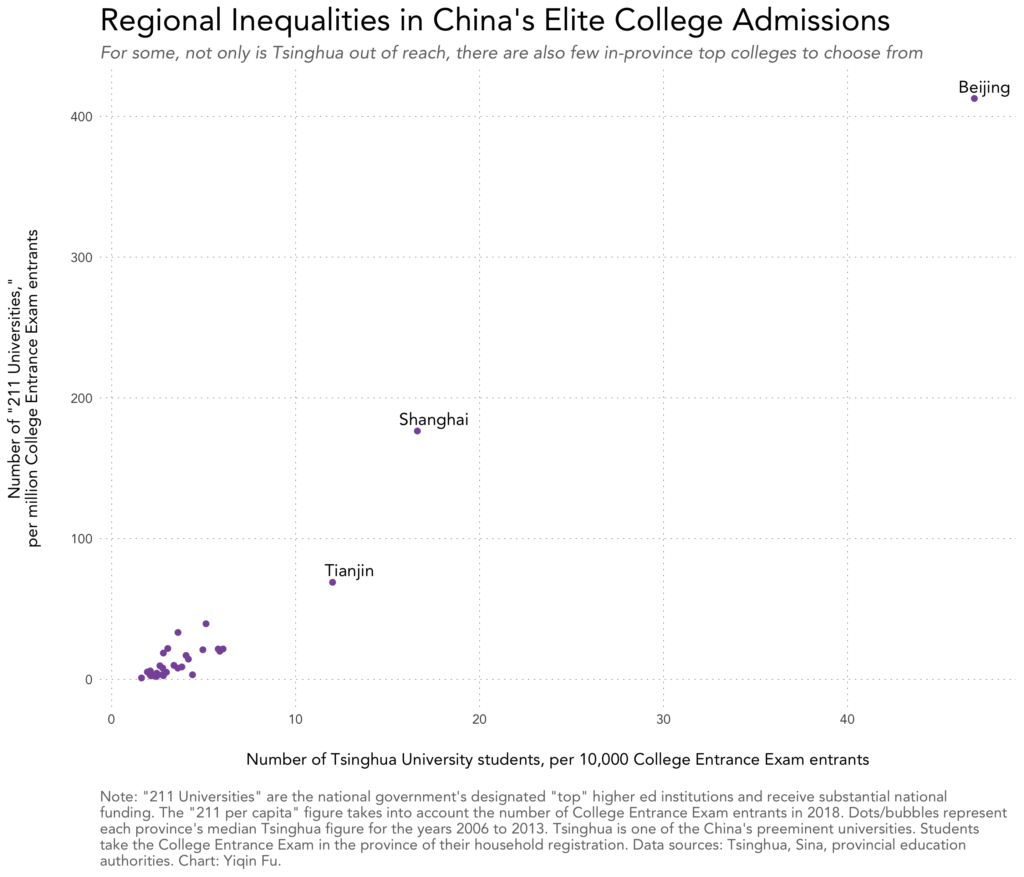

Universities often set enrollment quotas favoring students from their own region. Tsinghua University, for example, accepts far more students per capita from Beijing than from Shandong or Henan. This is not because the students are smarter in Beijing, but because the rules of the game are skewed.

The hukou system further deepens this inequality. Hukou is a household registration system in China that classifies citizens as either urban or rural residents, and determines their access to public services, including education. Children inherit their parents’ hukou status and can only take the Gaokao in the region where their hukou is registered. This means that children from migrant families living in big cities like Beijing must return to their hometowns to sit for the exam, even if they grew up and studied in the city.

To make matters more complicated, the Gaokao is not standardized across the country. Each province designs its own version of the exam, resulting in differences in curriculum, difficulty level, and chances of gaining admission to top universities. As a result, students from certain regions face a double burden: returning to a place they may barely know, and adjusting to an unfamiliar testing system that may not align with what they’ve learned in school—and is often even more competitive (because of more limited quota I mentioned above).

The Chinese government has actually attempted to reform the hukou system, including opening up the possibility for migrant children to take the Gaokao in the cities where they live. However, these policies vary greatly between regions and often require multiple documents, such as proof of residence, parental employment, and social insurance, that are not easy for migrant families to provide. Additionally, some regions impose restrictions on which universities these migrant students are allowed to apply to. As a result, even if they are permitted to take the Gaokao in their city of residence, they still don’t have the same access to top universities. Many students are thus still forced to return to their registered hometowns to sit for the exam, perpetuating inequalities that the reforms were meant to reduce.

And So Does Who You Are

Socioeconomic background is another fault line. Students from wealthier families enjoy better schools, more experienced teachers, and the all-important edge: private tutoring. The cram school industry in China is massive. In 2016, more than 75% of students were enrolled in some form of after-school tutoring.

In response, the government launched the 2021 “Double Reduction” policy, aiming to reduce students’ academic burden and regulate shadow education. But as long as the stakes of the Gaokao remain high, the demand for private tutoring persists—quietly shifting online or underground. The arms race continues, albeit more discreetly.

There’s also a cultural layer to this: the belief that “diligent study transforms fate.” This mantra gives Gaokao a moral weight, success is earned through struggle. And for many working-class families, this belief is the anchor of hope. But what happens when the struggle is uneven?

Learning from China’s experience

To address these inequalities, scholars and policymakers have proposed two main paths. First, affirmative action-style interventions, reserving seats for students from lower-income or rural backgrounds, offering bursaries, and subsidizing private tutoring access. These measures aim to narrow the preparation gap while preserving the Gaokao’s symbolic fairness.

Second, a broader cultural and structural shift: creating more alternative pathways beyond university, such as high-quality vocational education, and reshaping social narratives around success. Singapore and Germany offer useful models here. Not everyone needs to pass through the same gate to find a meaningful career.

Yet, these changes will take time. For Indonesia, the Gaokao experience offers a valuable cautionary tale. If we are to reintroduce a national exam like UN, we must do so with eyes wide open, acknowledging the structural inequalities in our education system and anticipating how a standardized test might widen or narrow those gaps. This means pairing the exam with policies that ensure more equal access to quality education: teacher support in disadvantaged schools, targeted subsidies for learning materials, and perhaps even adjusted benchmarks that take school context into account. Otherwise, we risk repeating the same patterns, where exams measure privilege as much as they do performance.

In the short term, the Gaokao remains both a ladder and a wall. For millions of Chinese students, it is still the best, and sometimes only, chance to climb out of inherited disadvantage. And while it may be flawed, it is one of the few systems in Chinese society still perceived to offer a semblance of fairness.

In the end, the question is not whether national exams like Gaokao or Indonesia’s UN should exist, but how to make their promise real. How to ensure that the gate doesn’t swing more easily for some than others. That, perhaps, is the test that truly matters.

Note: I wrote something related to this issue back in 2009 when I was still in high school. You can read it here: Program Baru, Masalah Baru. A reminder that this debate has been around for quite a while.